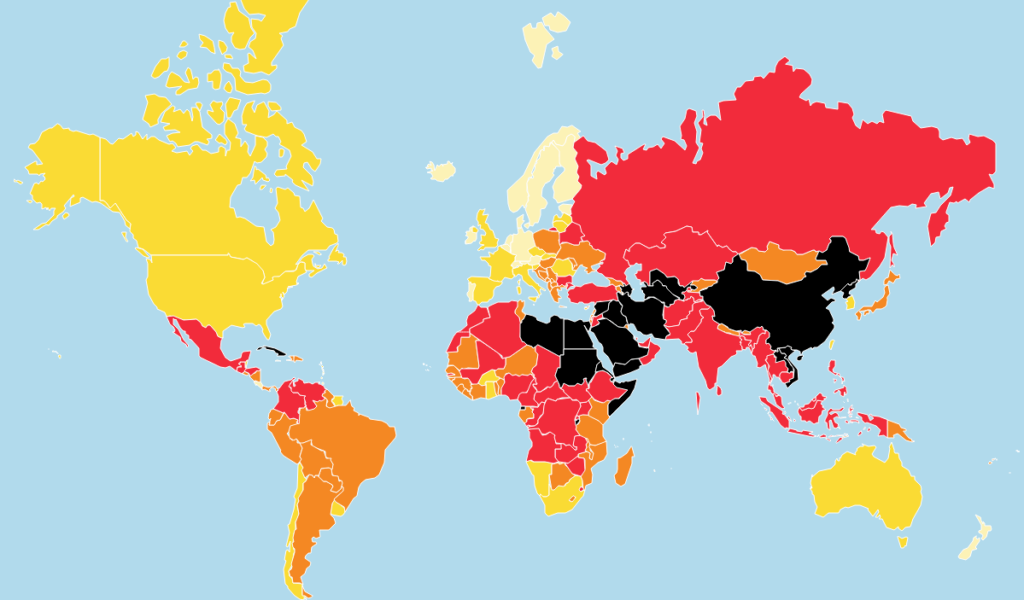

The nonprofit advocacy group Reporters Without Borders has released its annual World Press Freedom Index, a ranking and assessment of the metrics of press freedom in 180 countries. Coming at a time of global crisis, the 2020 Press Freedom Index took note of the immediate problems arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as more traditional threats to journalism. According to Reporters Without Borders representative Rebecca Vincent, government policy is not a stand-alone measurement, with the index instead focusing on how policies affect core areas that have an impact on press freedom, including levels of pluralism, media independence, the environment for media and self censorship, the legal framework, transparency, and the quality of infrastructure that supports news production.

The 2020 Press Freedom Index noted five main areas of crisis facing journalism even before the coronavirus pandemic presented new challenges. Reporters Without Borders, (known by its French acronym RSF) categorized the converging crises as a geopolitical crisis, a technological crisis, a democratic crisis, a crisis of trust, and an economic crisis. Noting that in the United States, half of all media jobs have disappeared over the past decade, the economic crisis facing media organizations before the pandemic is likely to bring even more hardship in the aftermath.

Among the rankings, Norway (1) retained its top position for the fourth year in a row, followed by Finland (2) and Denmark (3). Towards the bottom of the list, Eritrea ranked 178, followed by Turkmenistan (179) and, last on the list, North Korea (180).

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) narrowly missed the bottom three, ranking 177th on the list. RSF noted in a press release that “There is a clear correlation between suppression of media freedom in response to the coronavirus pandemic, and a country’s ranking in the index.” China, the organization said, had censored its COVID-19 coverage extensively, as had Iran (173) and Iraq (162). The index also highlighted emergency laws passed in Hungary (89) by Prime Minister Orbán, which carry a potential penalty of five years in prison for “false information,” which RSF called disproportionate and coercive.

“The public health crisis provides authoritarian governments with an opportunity to implement the notorious “shock doctrine” to take advantage of the fact that politics are on hold, the public is stunned, and protests are out of the question, in order to impose measures that would be impossible in normal times,” RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire said in a statement. “For this decisive decade not to be a disastrous one, people of goodwill, whoever they are, must campaign for journalists to be able to fulfill their role as society’s trusted third parties, which means they must have the capacity to do so.”

While many rankings don’t see much movement year by year, some policies and leadership changes can bring marked improvements. The 2020 Index saw the greatest leaps by Malaysia, which jumped from 123 to 101, and Maldives, which improved from 98th to 79th on the list, due to changes in government brought about by voters. Sudan also saw a leap from 2019, improving from 175 to 159, thanks largely to the removal of President Omar al-Bashir.

On the flip side, the largest negative changes were registered by Haiti (83 in 2020, from 62 in 2019), which has seen an uptick in targeted attacks on journalists while covering violent protests that have broken out in the country over the past two years. The African nation of Comoros fell 19 spots to land at 75th, while Benin was down 17 places to be ranked 113th.

The United States saw its rank improve by 3 places to 45th, however the index noted the increasingly hostile rhetoric towards journalists in both the US and Brazil (107), both of which are democracies. President Trump has repeatedly cast doubt on the trustworthiness of US news organizations, while also insulting reporters as nasty and calling media at large the enemy of the people, while in Brazil, president Bolsonaro has increased his media attacks since the coronavirus pandemic began, blaming reporters for creating hysteria and panic.

The index is compiled largely through metrics ascertained in part by a questionnaire created by industry experts and sent out in 20 languages. Those responses are supported by qualitative analysis to come up with a numerical score for each country ranked. The scores measure overall constraints and violations against free press.